PROGRESS MATTERS

PART DEUX

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

You’ve always had the power dear, you just had to learn it for yourself – Glinda the good witch.

I would suggest that the weekend before the A level results are published my demeanour changes. It’s taken me years to recognise this (or my wife to tells me) but now I am aware of it I at least try to manage it. I can only imagine that every secondary teacher in the country goes through a very similar experience. I find it difficult to sleep my anxiety levels rise and I question why I do such a stressful job! I cannot say that every year that I have taught my results reflect the effort I put in, there have been many highs and lows. The thought of having to justify my existence in front of the Headteacher can be debilitating and a dark side of teaching that very few people every see or experience but each year in the first term, Heads of Department and Faculties brace themselves for what can be a extremely stressful confrontation dressed up as an exams meeting. Your line manager / SLT link will accompany you to this meeting with their maths book tucked down the back of your trousers just in case the Head gets his cane out.

Ideally you enter into this meeting safe in the knowledge that it is your teaching that has clearly contributed to a young persons life chances and opportunities, you have also contributed to the school’s headline figures and value added (AV). When it all goes well you justify to yourself why you put yourself through this mental torture each year. It comes from knowing that the pupils you have taught are now off to pursue their dreams, this has got to be one of the most life affirming feelings one can have, I have not found its equal it in any other role.

In part one of this article when I stated that as humans our brains are designed to seek out new challenges, as educators each cohort provides us with a horizon of ever expanding possibilities. I know not every teacher views education like I do or will agree with me, but for me to teach each new cohort is like a ever expanding horizon, the goal that constantly recedes into the distance as I strive to meet the challenge, I truly believe teaching is a calling and the sharing new knowledge is transcendent goal. This doesn’t stop me from panicking thinking each year ‘how I am going to do it again!’. But this is the highest level of virtue I am able to challenge myself with, not cynical like Sisyphus forever rolling a bolder up a hill in the depths of Hades. As educators we have the honour of sharing our passion with pupils, witnessing them putting their lives together, watching them acquiring new skills, becoming richer and more abundant because of the power of knowledge.

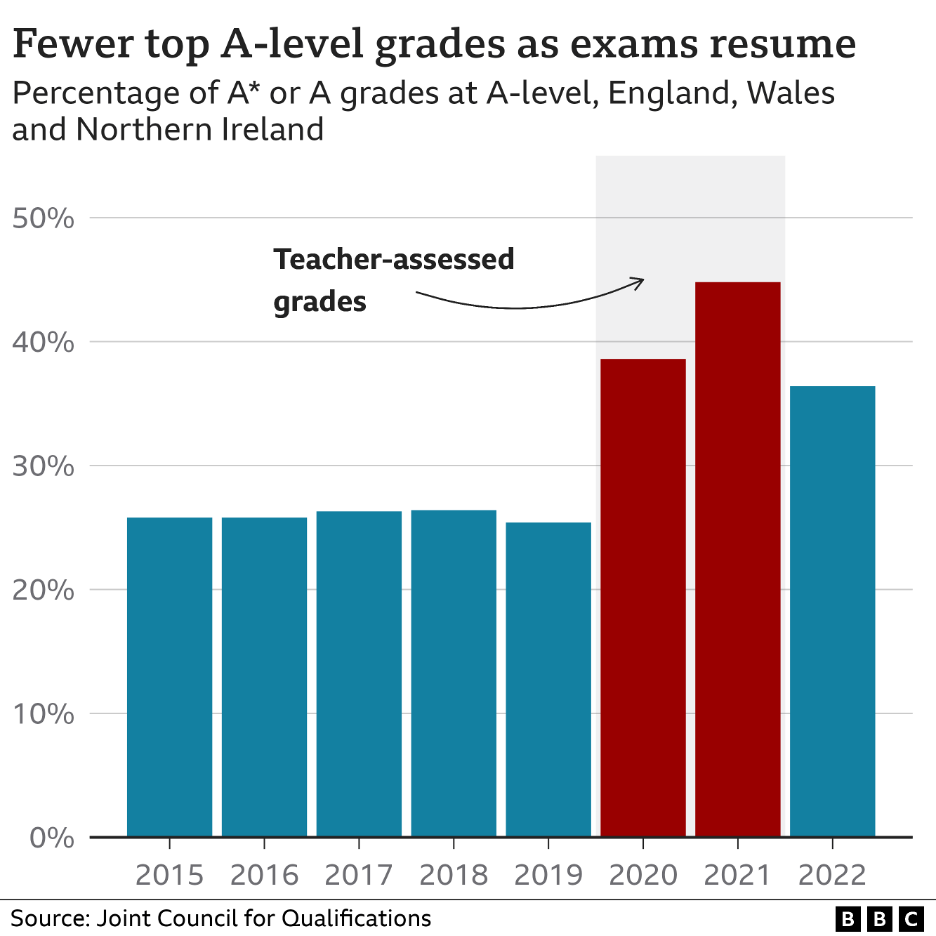

The good news is grades are still up compared to 2019, how comparable the exams were will be almost impossible to quantify. We cannot underestimate or forget the disruption that Covid has impacted upon pupils education since lockdown 2020, so. The government did introduced measures to counteract the unprecedented disruption to education such as advanced information about topics, however as predicted the A level grades were lower this year than the last 2 years of Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs). In England just under 36% of A-level entries gained A and A* grades this year, compared with 44.3% last year. GCSE students receiving top grades this year 9-7, is 26.3%.

In 2019, 25.4% were A* and A grades, this year (2022) 36.4% of A-levels were marked at A* and A compared to last year (2021) 44.8% of exams were graded A* or A. As I wrote about in my previous blog these are first public exams since 2019 that A-level grades have been based on. Approximately one in seven entries (14.6%) were awarded an A*, down from nearly one in five in 2021 (19.1%), but higher than the 2019 figure of 7.7%. A similar outcome for GCSEs 73.2% were graded at grades 4 and above this year. Again down from 77.1% last year but still 10 percentage points higher than in 2019, when it was 67.3%. As expected, GCSE results this year are lower, in England 75.3 per cent of all awards were at grade 4 or above, this is 3.8 percentage points lower than in 2021 but still 5.4 percentage points higher than in 2019.

This year Ofqual have in their own words offered an ‘unprecedented level of support.’ grade boundaries based on a profile that reflects a midpoint between 2021 and pre-pandemic grading advance information about the focus of the content of exams, some changes to coursework to reflect public health restrictions in place at the time students were doing their assessments.

A-level grades are lower because of the need to counteract the TAGs and sharp rise in top grades over the past two years. Ofqual said the approach was intended to bring grades closer to pre-pandemic levels, while reflecting “that we are in a pandemic recovery period and students’ education has been disrupted”.

A level Gender divides

Last Year the gender gap at A Level peaked and reached its highest level in 10 years, 46.4% for girls receiving an A* or As standing at compared to 41.7% for boys. Girls received more top grades than boys again this year, 37.4% of girls’ entries were given A* and A grades, compared with 35.2% of boys’ entries. Female students continue to outperform their male counterparts, but the lead has narrowed. Female students’ grades fell by 9.5 percentage points compared with 7 points among males. The proportion of girls with an A or higher was 37.4% this year, 2.2 percentage points ahead of their male counterparts, down from 4.8 percentage points last year, effectively halving the gender gap. However the overall number of students who achieved 3 A*s at A-level has also gone down, from 12,865 last year to 8,570 of them 57% were female compared to 43% males, which is a 14 percentage point difference.

GCSE Gender divides

78.7 per cent of entries from girls achieved a grade 4 in comparison with 71.9 per cent of boys. After TAGs the gap between boys and girls has remained the same, with the gap only slightly narrowing by 0.1 percentage points in comparison with last year. 2021 witnessed 82.5 per cent of entries from girls achieved a grade 4 or above in comparison with 75.6 per cent of entries from boys. In 2021 witnessed girls were being awarded 34.5 per cent 9-7 grade and boys 25.5 per cent were awarded a 9-7 grade. This year 30.7 per cent of entries from girls achieved a grade 9-7 compared to 23.3 per cent of entries from boys. This represents a narrowing of the gap from 2021 by 1.7 percentage points.

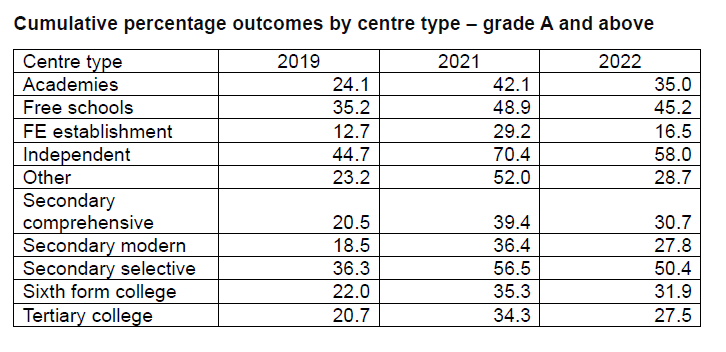

Independent divides

The gap has narrowed between Independent Schools and Comprehensive schools, this year it was a 27-percentage point difference in students graded A or above between Independent schools and secondary comprehensives compared to 31 percentage points last year. Last year we witnessed Independent schools across the UK, disproportionately benefiting from the proportion of top grades, you were almost twice as likely to receive an A* or an A at an independent school compared to a comprehensive. Grades rose 25.7 points to 70.4% compared to 2019, this year they were 12.4% lower in Independent schools with 58% achieving an A* or A. In 2021 39% of comprehensives school students achieved the top grades this year it was 8.7% lower at 30.7%.

As the Guardian Newspaper reported at the time “In one case of alleged grade inflation, Derby high school went from 6.5% of its entries awarded A* by examination in 2019 to nearly 54% awarded by assessment in 2021. North London Collegiate, a private girls school, nearly trebled the rate of A*s awarded so that more than 90% of its entries were assessed as A*s.”

Prof Lindsey Macmillan, of University College London’s Institute of Education, said the Department for Education (DfE) should allow researchers access to school and pupil data. However the publication of individual school results for A-levels and GCSEs, which the Department for Education (DfE) has so far refused to do. However if you look into both schools sited in the Guardian’s article Derby high school and North London Collegiate girls schools results this year there is a significant drop considerably more than 12.4% nationally.

GCSEs results for Independent schools 9-7 fell 8.2 per cent, far higher than the 2.7 per cent drop at comprehensives. Independent schools witnessed the biggest increase in GCSE results compared to other schools with TAGs. GCSEs graded 9-7 fell to 53 per cent from 61.2 per cent last year. TAGs witnessed GCSE grades increase from 47 per cent to 61.2 per cent between 2019 and 2021, a rise of 14.2 percentage points, double the rise in secondary comprehensives.

Regional divides

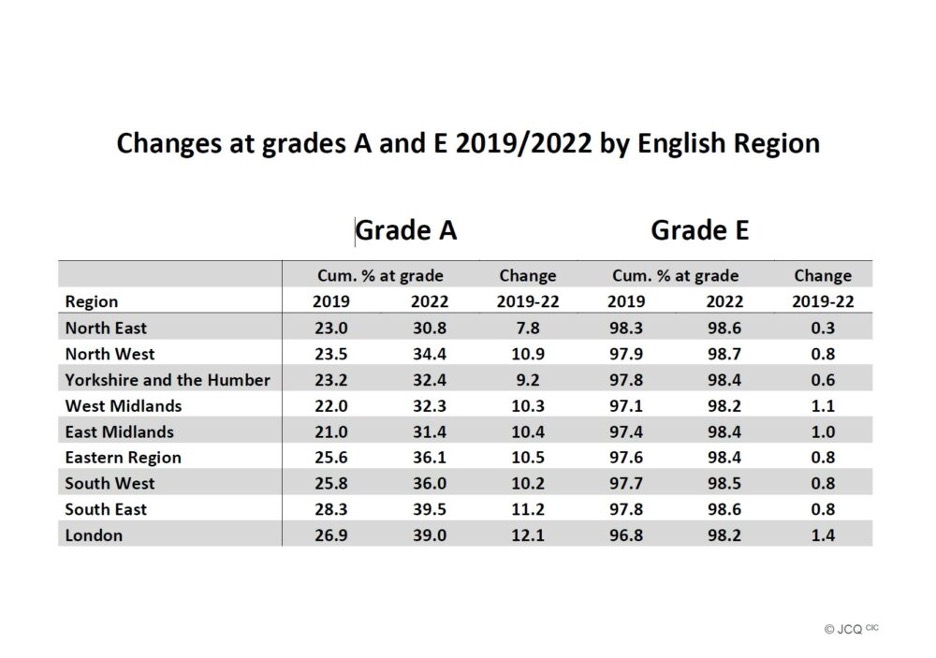

There were regional disparities in England, according to Ofqual. In London, 39% of A-level grades were A* and A, compared with 30.8% of grades in the north-east of England. Yorkshire and the Humber saw the second lowest percentage point change, at 9.2 per cent, while the southeast saw the second largest – 11.2. While the northeast fared worst in terms of the increase in top grades since 2019, other northern regions fell short this year.

GCSE results illustrate the north south divide, that regional disparities in pupils outcomes continue to persist. You are more likely to achieve a higher grade at GCSE if you live in London and the South East compared to the North East.

According to The Department for Education (DFE) ‘180,000 18-year-old students in England have had their place at their first choice of university confirmed. This is the largest number ever on record for an examination year, a 20% increase on 2019, when exams were last sat.’

Overall, 425,830 students of all ages and domiciles will be going onto university, including a record number of 18-year-olds from a disadvantaged background for an examination year. The gap between the most and least advantaged progressing to university has narrowed to a record low (from 2.29 in 2019 to 2.26 in 2022, and from 2.32 in 2021). For all years since 2010-11, the majority of undergraduate entrants have been female, standing at 56.5 per cent in 2020-21. This has increased by 0.9 percentage points, from 55.7 per cent in 2019-20. The proportion of UK domiciled undergraduate entrants who are white has fallen 8.3 percentage points, from 78.7 per cent in 2010-11 to 70.4 per cent in 2020-21.

The man behind the curtain

When I completed my Masters I would often refer to data as the man behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz. Like the Wizard of Oz, data is able to scare most people away from it without challenging it, they are afraid of its strong commanding voice and overwhelmed by the magnitude of it. Schools are data rich environments and therefore the magnitude of the data becomes overwhelming, the art of using data successfully stems from understanding what are the attributes that have the biggest impact on pupil progress, knowing when and how to intervene. Data should be as easy to read as a scoreboard at a sports match and take you less than 3 seconds to workout who is ahead, otherwise it’s not fit for purpose poorly designed or hiding something.

For my Masters I ostensibly wrote about pupil tracking data and now ironically as I pointed out in part on, OFSTED will no longer look at schools’ internal data when making a value judgement on the quality of teaching and learning. However as this and my previous blog I have illustrated is that statics are important at every level in Education, being able to see the macro and micro indicators are fundamental to the success of pupils and schools respectively, but more importantly not to hide behind the curtain of lies because all it takes is a small yappy dog to pull back the screen and reveal the truth.

To measure pupils’ performances totally based on A-E or 1-9 is not a valid measure of education because not everyone is blessed with the same starting point, ambitions or path they are on. However colleges and universities still use it as entry criteria to be accepted on their courses. Arguably results themselves are not a valid measure as the last few years have highlighted. Often they do not give a full picture Covid or otherwise, pupils have different journeys and starting points weather they be cultural,social, economic or geographic. Moreover they are definitely a true indicator regarding the quality of teaching and learning a pupil has received, standardised tests make the implicit assumption that everyone has received the same standard of education, or the same access and opportunities which is never going to be the case.

A more reliable summative measure of pupil performance is Value Added. Value-added measures, or growth measures, are used to estimate or quantify how much of a positive (or negative) effect individual teachers have on student learning during the course of a given keystage. Progress 8 is a type of ‘value-added’ measure that indicates how much pupils at a secondary school have improved over a five year period when compared to a government-calculated expected level of improvement. It takes a pupil’s performance in relation to their peers at primary school level, compares it with their performance at GCSEs and then, after some mental arithmetic, establishes whether the individual has progressed at, above or below the expected level.

Education in my experience in schools chose a very narrow set of skills to measure pupils’ ability. Education shouldn’t be a first passed the post, the truest measure is ‘progress over time’. The current system is increasingly in my experience lending itself to pub-quiz style knowledge that is superficial, lacks depth, understanding and mastery. The ability to regurgitate standard-form information learnt by route must be redundant by now – Ask Alexa or Siri, you wouldn’t dare call either of these devices intelligent would you?

Sorry, I didn’t quite get that can you repeat the question……….?